- Home

- Guidelines

- Innovation

-

Education

- Study Days & Courses

- STAR Simulation App

- Faculty Resources

- Videos >

- Respiratory Videos (High flow, Tracheostomies, Chest drains, and sleep studies)

- Speciality Training Resources

- Paediatric Long Term Ventilation Team

- Life Support Resources

- #PedsCards Against Humanity

- Bronchiolitis Surge Resources

- Other Educational Opportunities

- Research

- Conference

-

Trainees

- Preceptorships

-

Networks

- Wessex Children's and Young Adults' Palliative Care Network

- PREMIER - Paediatric Regional Emergency Medicine Innovation, Education & Research Network

- Wessex Allergy Network

- Wessex Paediatric Endocrine Network

- Wessex Diabetes Network

- Clinical Ethics >

- TV and Wessex Neonatal ODN

- Regional Referrals to Specialist Services >

- Search

Days

Hours

Minutes

Seconds

This guideline is now due a review. Please continue to follow the enclosed guidance check any national guidance that may exist

Management of Malaria in Children

Summary

- Call paediatric ID team (Southampton) if any concerns on 07824417993

- Malaria is an imported parasitic infection transmitted to humans by the bite of female Anopheles mosquitoes and is caused by five species of Plasmodium - falciparum, vivax, ovale, malariae or knowlesi.

- P. falciparum is the most common cause of severe malaria in humans but P. knowlesi, and more rarely P. vivax can also cause severe illness.

- Severe malaria is a medical emergency. Children with malaria can deteriorate extremely quickly, especially those with comorbidities. The diagnosis must be confirmed urgently and treatment started as soon as possible.

- Malaria should be ruled out in any child with fever (current or recent history) returning from a malaria endemic area within the last year, even if anti-malarial chemoprophylaxis was taken. Symptoms may be non-specific and “flu-like” including malaise, headache, rigors, cough, abdominal pain, myalgia, vomiting or diarrhoea.

- Incubation period of malaria between 7 days and 3 months

- Up-to-date information on malaria endemicity, drug resistance patterns and chemoprophylaxis recommendations is available at:

- All cases of malaria should be confirmed by parasitological tests (microscopy or Illumigene (LAMP technology) for malarial parasites and Rapid Diagnostic Test (RDT). Malaria cannot be clinically distinguished from other causes of fever.

- Intravenous (IV) artesunate is the treatment of choice for all children with severe malaria. If there is an anticipated delay in administering artesunate, IV quinine should be used until artesunate is available (NOTE: there is currently a long standing supply issue with IV quinine meaning that it may be challenging to obtain.) Broad spectrum antibiotics (e.g. IV ceftriaxone) should be administered to children presenting with severe malaria to cover for sepsis after appropriate septic screen (see full guideline below).

- Contact pharmacist to obtain IV artesunate. They should know where to obtain IV artesunate urgently out of hours:

- Southampton – stored in emergency drug cupboard (key from security)

- Chichester - kept in pharmacy. Out of hours need to call the on-call pharmacist to come in to access.

- Dorchester – available in Yeovil and Bournemouth; agreement for artesunate to be urgently sent by taxi.

- Specialist Paediatric Infectious Diseases advice should be obtained as early as possible and cases of severe malaria should ideally be managed in a tertiary centre with paediatric intensive care facilities.

Definitions

Severe Malaria

It is defined as the presence of one or more of impaired consciousness or seizure, prostration, acidosis, hypoglycaemia, severe anaemia, renal impairment, jaundice, pulmonary oedema, bleeding sites, shock, parasitaemia >2% (See section 4.4 for more details).

Uncomplicated malaria

Malaria with no severe features.

Artemisinin-based combination Therapy (ACT)

Combination of an artemisinin derivative and another class of antimalarial drug. Unless otherwise specified, this refers to artemetherlumefantrine (RiametÒ) which is the preferred ACT for the purpose of this guideline.

Asymptomatic parasitaemia

Presence of asexual parasites in the blood without symptoms. This may be seen in children who live in malaria endemic areas and have a degree of acquired immunity

Cerebral malaria

Encephalopathy caused by severe P. falciparum malaria presenting as impaired conscious level, seizures, posturing and altered respiratory pattern. It is associated with a high mortality rate.

Asexual stages

The asexual stages of the parasite (rings, trophozoites, and schizonts) are the only stages which cause symptoms. These are the parasites which are counted when determining the percentage parasitaemia.

Gametocytes

Sexual stages of the parasite which do not cause symptoms. They may circulate in blood for some time after treatment of malaria. They indicate recent infection, but do not indicate treatment failure if they persist after clearance of asexual stages.

Hypnozoites

Liver stages exclusively of P. vivax and P. ovale that remain dormant and may result in relapse of malaria months after initial infection. Not detectable by blood test.

Rapid diagnostic test (RDT)

Rapid test for Plasmodium antigens, usually performed in conjunction with blood films. j. APLS – Advanced Paediatric Life Support k. G6PD – Glucose 6 phosphate dehydrogenase

PfHRP2

Plasmodium falciparum histidine rich protein 2 m. pLDH – parasite lactate dehydrogenase

Parasitaemia

The presence of parasites in the blood, quantified as the percentage red blood cells infected by parasites

RDT

Rapid Diagnostic Test

It is defined as the presence of one or more of impaired consciousness or seizure, prostration, acidosis, hypoglycaemia, severe anaemia, renal impairment, jaundice, pulmonary oedema, bleeding sites, shock, parasitaemia >2% (See section 4.4 for more details).

Uncomplicated malaria

Malaria with no severe features.

Artemisinin-based combination Therapy (ACT)

Combination of an artemisinin derivative and another class of antimalarial drug. Unless otherwise specified, this refers to artemetherlumefantrine (RiametÒ) which is the preferred ACT for the purpose of this guideline.

Asymptomatic parasitaemia

Presence of asexual parasites in the blood without symptoms. This may be seen in children who live in malaria endemic areas and have a degree of acquired immunity

Cerebral malaria

Encephalopathy caused by severe P. falciparum malaria presenting as impaired conscious level, seizures, posturing and altered respiratory pattern. It is associated with a high mortality rate.

Asexual stages

The asexual stages of the parasite (rings, trophozoites, and schizonts) are the only stages which cause symptoms. These are the parasites which are counted when determining the percentage parasitaemia.

Gametocytes

Sexual stages of the parasite which do not cause symptoms. They may circulate in blood for some time after treatment of malaria. They indicate recent infection, but do not indicate treatment failure if they persist after clearance of asexual stages.

Hypnozoites

Liver stages exclusively of P. vivax and P. ovale that remain dormant and may result in relapse of malaria months after initial infection. Not detectable by blood test.

Rapid diagnostic test (RDT)

Rapid test for Plasmodium antigens, usually performed in conjunction with blood films. j. APLS – Advanced Paediatric Life Support k. G6PD – Glucose 6 phosphate dehydrogenase

PfHRP2

Plasmodium falciparum histidine rich protein 2 m. pLDH – parasite lactate dehydrogenase

Parasitaemia

The presence of parasites in the blood, quantified as the percentage red blood cells infected by parasites

RDT

Rapid Diagnostic Test

Scope

This guideline is to be used by staff working within Acute Children’s Services across Wessex. It should be used in conjunction with advice from a consultant in Paediatric Infectious Diseases (contactable via 07824417993).

Guideline

Malaria is notifiable and Public Health England should be informed once diagnosis is confirmed (https://www.gov.uk/health-protection-team).

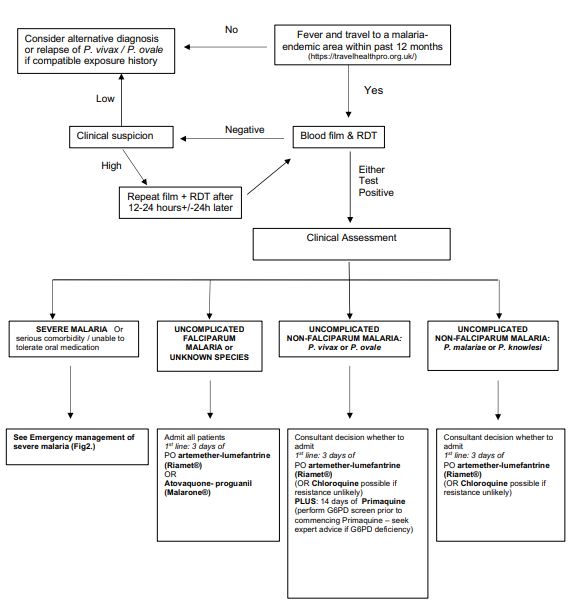

Diagnosis

Differential Diagnosis

It is important to remember that fever in a returning traveller can be caused by the same organisms as we see causing severe illness in any child (see list below). Co-infections are common especially in severe malaria and should always be considered in overseas visitors and returning travellers. Specifically, P. falciparum malaria increases the risk of enteric Gram-negative bacteraemia. Thus the detection of Plasmodium parasites does not mean that malaria is the only cause of the illness and a high index of suspicion of co-infection should be maintained, particularly in a seriously ill child.

Whilst any parasitaemia should be treated, alternative diagnoses should be considered and excluded including:

Investigations

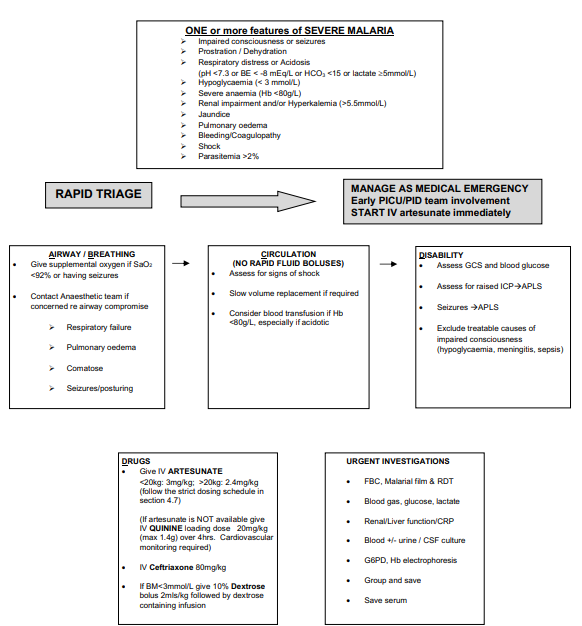

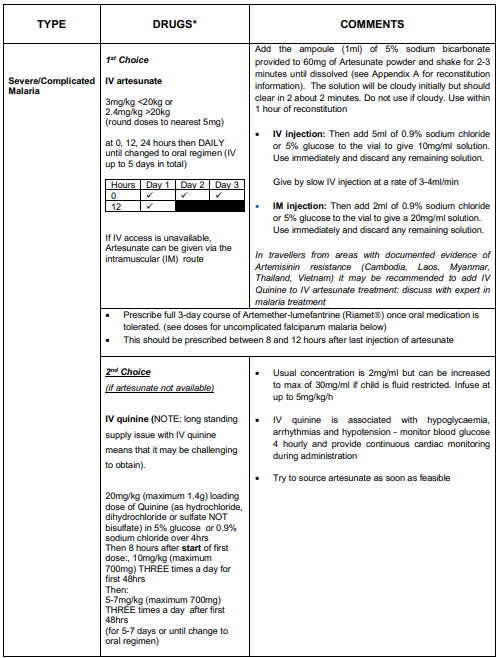

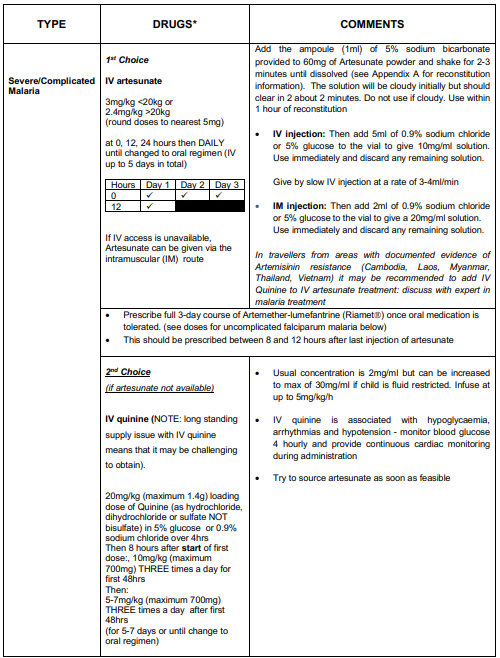

Management of SEVERE MALARIA (see Flowchart 2. for management, see Table 2. drug doses)

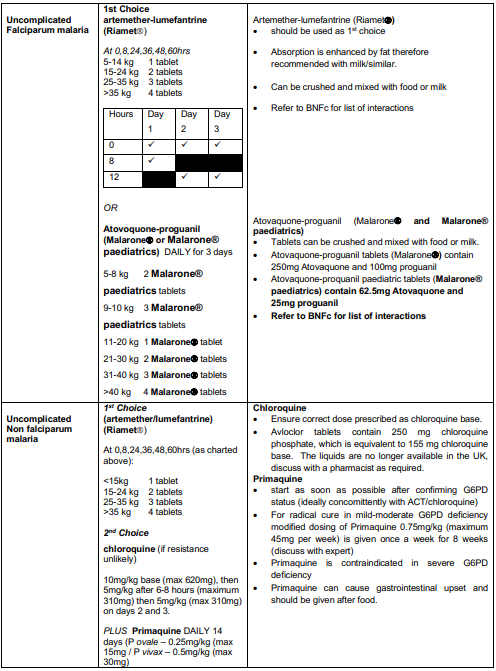

Management of uncomplicated malaria – Divided into P. falciparum and non-Falciparum and defined as absence of features of severe malaria

Uncomplicated P. falciparum malaria

Uncomplicated non-falciparum malaria

Monitoring of parasitaemia and laboratory tests

Diagnosis

- A full travel history must be taken, including: dates of all travel, detailed itinerary, vaccinations, chemoprophylaxis, bite avoidance measures, and any treatment received while abroad. This history will aid the interpretation of diagnostic tests for malaria and inform the differential diagnosis.

- Identification of Plasmodium parasites on blood film is the gold standard for diagnosis (thick and thin films). These allow speciation, staging and quantification of parasitaemia.

- Gametocytes (the sexual stage of Plasmodium) may be detected in the blood of individuals who live in a malaria endemic country – they do not cause illness unless there are also asexual stage parasites and should NOT be assumed to be the cause of illness.

- Results should be available within 2 hours. Ensure the lab has been informed to expect the sample and its delivery to the lab is expedited.

- If the initial test is negative, and index of suspicion high (e.g. ongoing fever) repeat blood film (in conjunction with an RDT) after 12-24 hours and again after another 24 hours. This may be especially relevant in cases where some chemoprophylaxis was given. Repeat testing is not required if there is a low clinical threshold for malaria, fever has resolved spontaneously and initial blood film and RDT are negative.

- Rapid diagnostic tests (RDT) have a high sensitivity (except for P. knowlesi) and specificity and are performed on all blood samples being tested for malaria parasites. These are particularly useful in providing a rapid result, where malarial blood film examination is likely to be delayed. RDTs can remain positive for several weeks after recovery, therefore they are not useful for monitoring response to treatment.

- The results from the malaria RDTs are reported as either 'Negative' or 'Positive'

- RDTs should always be interpreted in conjunction with blood film results

- In travellers from Indonesia, Malaysia and surrounding countries in South East Asia, a suspicion of P. knowlesi malaria should be maintained until negative blood films exclude parasitaemia. As P. knowlesi and P. malariae have a similar appearance on microscopy, children returning from these areas should be treated as for P. knowlesi if either of these parasites is reported on the blood film (based on clinical features i.e. severe or uncomplicated.)

Differential Diagnosis

It is important to remember that fever in a returning traveller can be caused by the same organisms as we see causing severe illness in any child (see list below). Co-infections are common especially in severe malaria and should always be considered in overseas visitors and returning travellers. Specifically, P. falciparum malaria increases the risk of enteric Gram-negative bacteraemia. Thus the detection of Plasmodium parasites does not mean that malaria is the only cause of the illness and a high index of suspicion of co-infection should be maintained, particularly in a seriously ill child.

Whilst any parasitaemia should be treated, alternative diagnoses should be considered and excluded including:

- Typhoid and other bacterial infections

- Common viral infections e.g. Influenza

- Rarer tropical infections e.g. viral haemorrhagic fever

Investigations

- FBC, Blood film for malarial parasites and malaria rapid diagnostic test o

- Note that thrombocytopenia is a typical feature in malaria

- Category 4/query viral haemorrhagic fever samples will still be processed urgently and this should not delay testing; discuss with the on-call microbiologist who can risk assess to decide whether samples need to be processed in safety cabinet

- Blood gas (including lactate)

- Blood glucose

- Renal function, liver function, CRP

- Additional investigations based on clinical features and differentials

- G6PD level (expedite result if P. vivax or P. ovale confirmed and before giving primaquine)

- Sickle screen (increased risk of severe malaria in children with functional asplenia)

- Clotting (all severe cases)

- Group and save (all severe cases)

- Save serum (serology and virology)

- Blood culture (all severe cases)

- Chest x-ray • Cultures – Urine, CSF, Throat

- Viral panel – CSF, Throat

Management of SEVERE MALARIA (see Flowchart 2. for management, see Table 2. drug doses)

- Manage as a MEDICAL EMERGENCY. ONE or more of the following features

- Impaired consciousness or seizures

- Prostration

- Clinical dehydration

- Respiratory distress or Acidosis (pH <7.3 or BE < -8 mEq/L or HCO3 <15 or lactate ³5mmol/L)

- Hypoglycaemia (< 3 mmol/L)

- Severe anaemia (Hb <80g/L)

- Renal impairment and/or Hyperkalaemia (>5.5mmol/l)

- Jaundice (>50 µmol/L)

- Pulmonary oedema – SaO2 < 92% or suggestive x-ray associated with clinical signs

- Significant bleeding – e.g. nose, gums, venepuncture sites, haematemesis, malaena

- Shock: CRT ³ 3, temperature gradient on legs, cool peripheries. May have compensated (normal BP) or decompensated shock (BP < 70 systolic).

- Parasitaemia >2% (parasitaemia is a very poor predictor of outcome and the relevance of the parasite counts depends upon prior immunity/exposure).

- Provide supportive care in line with the APLS guidelines 2015, EXCEPT FOR FLUID RESUSCITATION (SEE BELOW), and manage in a high dependency or paediatric intensive care unit.

- Seek early expert advice from a paediatric infectious diseases consultant who is experienced in the management of severe malaria.

- Provide oxygen to maintain saturations ³92%

- RAPID FLUID BOLUS IS CONTRAINDICATED. Judicious and slow fluid resuscitation is recommended in children presenting with shock and should be evaluated on an individual basis in conjunction with paediatric intensive care and infectious diseases consultants.

- Do not base decision about fluid resuscitation on lactate levels – lactate is usually raised in malaria due to obstructed blood vessels, not shock.

- Blood transfusion should be performed if severe anaemia is present (especially if there is also metabolic acidosis). Thrombocytopenia is common, and platelet transfusion is not indicated unless there is active bleeding. Severe coagulopathy or spontaneous bleeding are rare, and should be managed in conjunction with expert haematology advice. Exchange transfusion is not recommended.

- Watch for signs of raised ICP and institute neuroprotective measures accordingly

- IV artesunate is the antimalarial drug of choice for severe malaria. It should be given as soon as the diagnosis is confirmed in children with severe features.

- Where can I find artesunate?

- Usually found in Emergency drug cupboard or in adult ED

- Once prescribed, request supplies from pharmacy to enable a second dose 12 hours later.

- If IV artesunate is likely to be delayed/not available, IV quinine should be administered as soon as possible as a second line antimalarial drug (note risk of hypoglycaemia with IV quinine). This should be switched to IV artesunate as soon as it is available.

- All children with severe malaria should be commenced on broad spectrum antibiotics (IV ceftriaxone is a reasonable empirical choice)

- IV artesunate / quinine can be switched to oral artemether-lumefantrine (Riamet) or atovaquone-proguanil (Malarone) after at least 24 hours and when child is able to tolerate orally. A 3 day course of Riamet (or Malarone) should be completed.

Management of uncomplicated malaria – Divided into P. falciparum and non-Falciparum and defined as absence of features of severe malaria

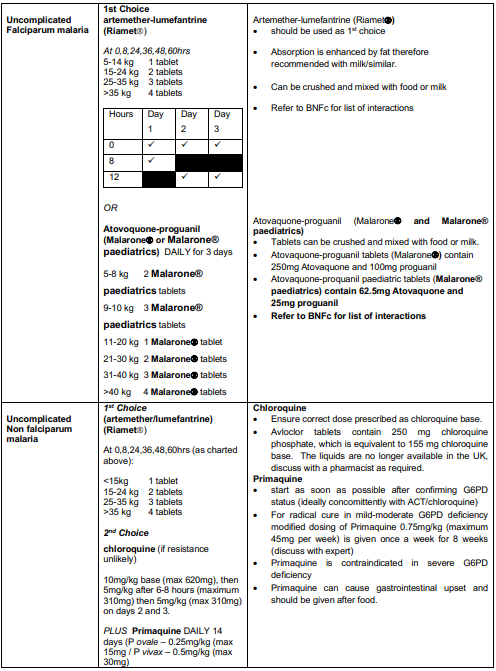

Uncomplicated P. falciparum malaria

- Good practice is? to admit all children with uncomplicated P. falciparum malaria.

- Treat with IV artesunate if not tolerating/vomiting oral medication.

- Artemether-lumefantrine (Riamet) should be used as first line treatment for a total of 3 days to complete a full course. If not available or contraindicated due to hypersensitivity, atovaquone-proguanil (Malarone) may be used instead.

- Screen for co-existing infections

Uncomplicated non-falciparum malaria

- Caused by Plasmodium species other than P. falciparum

- Consultant decision whether to admit based on clinical condition. Need to ensure appropriate safety netting and compliance with full course of treatment

- ACT (Riamet) is the most universally effective treatment and is given for 3 days.

- Chloroquine may be used in travellers from areas where there is no/very low chloroquine resistance. The treatment duration is 3 days as for ACT.

- Patients with P. vivax and P. ovale malaria require treatment with primaquine for radical cure, in order to prevent relapse through hypnozoites in the liver. This should be started as soon as G6PD status has been confirmed (ideally concomitantly with ACT/chloroquine) to minimise the risk of relapse.

- Primaquine is contraindicated in patients with severe G6PD deficiency. Test all patients with these infections for G6PD enzyme activity. Expert advice should be sought if there is evidence of G6PD deficiency

Monitoring of parasitaemia and laboratory tests

- Perform daily parasite counts for in-patients

- Note that parasitaemia may increase over the first 24-36 hours (especially in severe malaria) and does not indicate treatment failure or resistance

- Continue monitoring until asexual blood stage parasites are no longer seen on the blood film

- Note that gametocytes (sexual stages) may persist or appear during or after treatment – these do not indicate treatment failure

- Note that parasitaemia may increase over the first 24-36 hours (especially in severe malaria) and does not indicate treatment failure or resistance

- Perform additional monitoring of blood parameters as indicated by initial values

- Check FBC 2 weeks after presentation if treated with iv artesunate, as there is often a delayed fall in haemoglobin which may be clinically significant

References

- DYER, E., WATERFIELD, T. & EISENHUT, M. 2016. How to interpret malaria tests. Arch Dis Child Educ Pract Ed, 101, 96-101.

- KIANG, K. M., BRYANT, P. A., SHINGADIA, D., LADHANI, S., STEER, A. C. & BURGNER, D. 2013. The treatment of imported malaria in children: an update. Arch Dis Child Educ Pract Ed, 98, 7-15.

- LALLOO, D. G., SHINGADIA, D., BELL, D. J., BEECHING, N. J., WHITTY, C. J., CHIODINI, P. L. & PHE Advisory Committee on Malaria Prevention in UK Travellers. UK malaria treatment guidelines 2016. J Infect, 72, 635-49.

- MAITLAND, K., KIGULI, S., OPOKA, R. O., ENGORU, C., OLUPOT-OLUPOT, P., AKECH, S. O., NYEKO, R., MTOVE, G., REYBURN, H., LANG, T., BRENT, B., EVANS, J. A., TIBENDERANA, J. K., CRAWLEY, J., RUSSELL, E. C., LEVIN, M., BABIKER, A. G., GIBB, D. M. & GROUP, F. T. 2011. Mortality after fluid bolus in African children with severe infection. N Engl J Med, 364, 2483- 95.

- WORLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION 2016. Guidelines for the treatment of malaria. Third Edition. World Health Organization, Geneva.

|

Document Version:

1.2 Lead Authors: Dr Sanjay Patel, Consultant Paediatric Infectious Disease, UHS |

Approving Network:

Wessex Infectious Diseases Network Date of Approval: May 2022 Review Due: May 2025 |

PIER Contact |

|

- Home

- Guidelines

- Innovation

-

Education

- Study Days & Courses

- STAR Simulation App

- Faculty Resources

- Videos >

- Respiratory Videos (High flow, Tracheostomies, Chest drains, and sleep studies)

- Speciality Training Resources

- Paediatric Long Term Ventilation Team

- Life Support Resources

- #PedsCards Against Humanity

- Bronchiolitis Surge Resources

- Other Educational Opportunities

- Research

- Conference

-

Trainees

- Preceptorships

-

Networks

- Wessex Children's and Young Adults' Palliative Care Network

- PREMIER - Paediatric Regional Emergency Medicine Innovation, Education & Research Network

- Wessex Allergy Network

- Wessex Paediatric Endocrine Network

- Wessex Diabetes Network

- Clinical Ethics >

- TV and Wessex Neonatal ODN

- Regional Referrals to Specialist Services >

- Search